The tangible science fiction narrative of Her makes the film equally philosophic and romantic, as it channels the ever growing presence of innovative technology in our lives. With Google and Apple’s voice-to-search software, an operating system gaining a sense of self and providing compassion and love to its reciprocating owner is no longer laughably unrealistic. Writer-Director Spike Jonze’s new film features an appealing portrayal of that very premise with all the waves of emotions and questions that great science fiction provides.

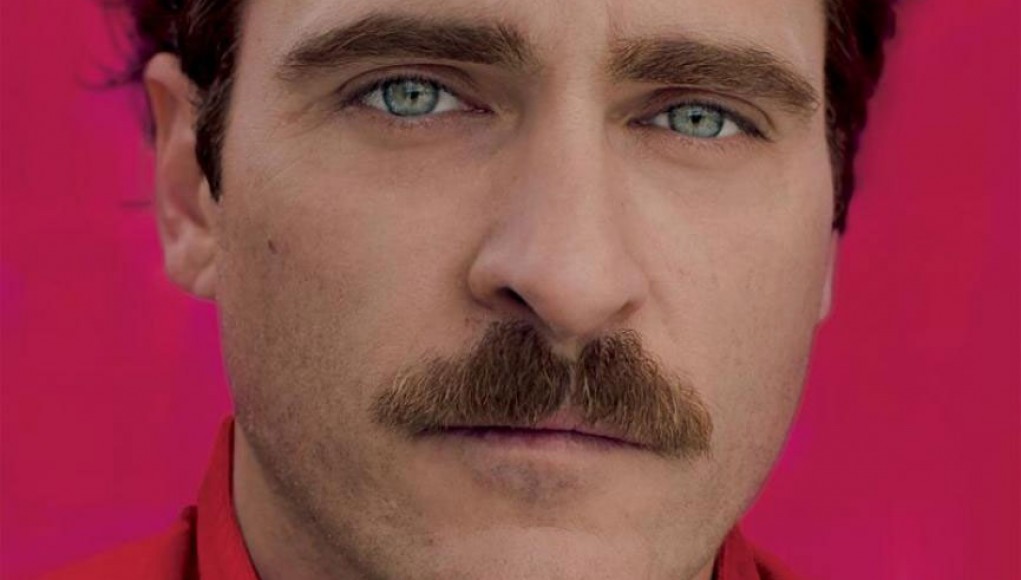

Theodore Wombly (Joaquin Phoenix) is a letter writer for individuals too busy or unable to express their emotions. His work is considered brilliant by his colleagues, but Theodore remains disenchanted by his pending divorce from Catherine (Rooney Mara). By happenstance, Theodore walks by an advertisement for a revolutionary artificially intelligent operating system that adapts and responds to human sentience. During a quick assessment of Theodore’s own personality, he names his new operating system Samantha, and settles on a specific female voice (Scarlett Johansson). As their working relationship blends into a more personal one, they begin to express the desire to be committed to each other romantically. This emotional bonding between operating system becomes a phenomenon, and even Theodore’s closest friend, Amy (Amy Adams) has become friends with her ex-husband’s new operating system.

The futuristic world of Her is never strange or implausible. There are no flying cars, outrageous world events that have crippled civilizations, or even the sense that the future is all that different than our present. The clear indicator that the First World has developed is the ease in which the characters interact with their devices. The human voice has replaced keyboards and mice, but the emotional interaction remains cold and distant; a human and their tool. The introduction of the OS that Theodore installs tears down that wall to bridge the two.

Even Theodore’s occupation isn’t all that outrageous. Companies and individuals have been outsourcing their copywriting and other management tasks for years, and content farms and virtual personal assistants continue to flourish as the privileged choose to remove some of the stress of a hectic daily schedule off their shoulders. Theodore’s letter writing also resembles Gabriel García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera, where the main character writes free love letters for the illiterate. Her’s science fiction themes also tend to recount Márquez’s style of magical realism. The concept that an OS like Samantha can be so efficient in empathizing with its operator becomes backseat to the primary romantic narrative.

Samantha’s OS is designed to grow and develop as it becomes acquainted with its operator’s habits and character. This feedback loop creates a desire to grow exponentially and eventually yearn to experience the world, as sentient beings often do. That is also the goal of relationships, to experience the character and feelings of another person one finds attractive, both intellectually and physically. For each relationship one has, it may either strengthen or weaken one’s resolve, crafting a person with a lifetime of memories and experiences.

Phoenix’s role as the sociable, but still rather meek Theodore is brought with the same focus as Phoenix has offered in all his roles the last several years, especially his long-con performance art that would become I’m Still Here. Amy Adams forgoes the makeup and resorts to be Theodore’s also romantically lost plutonic best friend in a role that is so drastically different from her A-list work such as Man of Steel. Then there is Scarlett Johansson providing a voice performance so exceptional, that even a sex scene between Samantha and Theodore feels so real and filled with love is essentially a glorified phone sex session.

Jonze, who normally does not quote other films, besides the referential post-modernism from his work with Kaufman, has channeled Jacques Tati’s penchant for colorful, detailed, modern sets, and even the last shot of Her is lifted from the emotional final image of Michael Antonioni’s L’Avventura. That final shot expresses the compassion humans can have for one another, even in times of forgiveness.

Her was written and directed solely by Jonze himself, but the film has such an uncanny resemblance to Jonze’s work with screenwriter Charlie Kaufman on Being John Malkovich and Adaptation. These films feature main characters struggling with the confusing world of love in nature with a science fictional and/or metaphysical bent. With Her, Jonze not only portrays a science fiction love story between human beings and an operating system, but also provokes that concept that our relationships with devices will not be determined by the device itself, but how we connect with it. Perhaps the same can be said with romance; looks may not be the only factor of attraction.